From Prince to Buddha

A royal life surrendered, a spiritual quest embraced—Buddha's transformation reveals that true freedom lies not in power, but in understanding and liberation.

Birth of Buddha

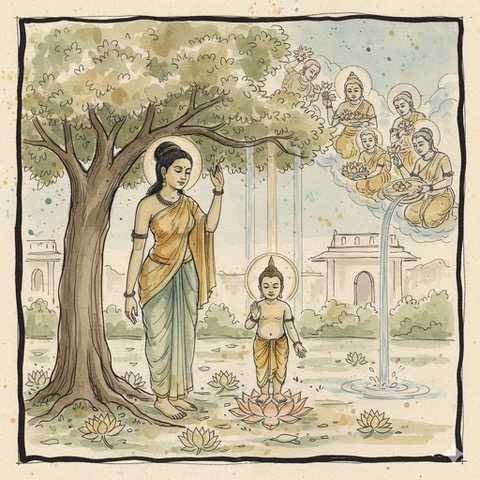

Queen Maya was the wife of Suddhodana, the virtuous ruler of the small kingdom of Kapilavastu. One night she had a wondrous dream: a radiant Bodhisattva descended from heaven riding a white elephant, the symbol of purity and divine kingship. The elephant circled her three times and gently touched her right side with its trunk, and in that blessed moment she conceived the child who would become the Buddha. His birth was said to be equally miraculous. On the eighth day of the fourth lunar month, while Queen Maya was walking peacefully in the beautiful Lumbini Garden, south of the Himalayas, she paused beneath a flowering śāla (aśoka) tree and raised her right arm to pluck a blossom. At that instant the infant Buddha emerged painlessly from her side, without blood or suffering, bathed in a serene, otherworldly light. Immediately after his birth he took seven sure steps toward the north, lotuses blooming beneath his feet, and proclaimed in a clear, resonant voice that this would be his final incarnation and that he had come into the world to guide all beings toward freedom from suffering. Witnesses were filled with awe, sensing that this was no ordinary child but a world-honored one. From the dream to the gentle birth, each sign was remembered as a symbol of purity, deep compassion, and the awakening he would one day share with all.

Childhood of Buddha

The young prince Siddhartha was born into the ancient Sakya clan, whose royal symbol was the lion; because of this, he is often remembered as “Sakyamuni,” the sage of the Sakyas, or “Sakyasimha,” the lion of the Sakyas. His father, King Suddhodana, belonged to the proud warrior caste and dreamed that his son would one day become a powerful ruler. Soon after Siddhartha’s birth, however, the wise sage Asita visited the palace and, seeing the marks of greatness on the infant, foretold that the child would grow up not as a worldly king but as a holy man who would seek truth for the benefit of all. Troubled by this prophecy and afraid of losing his heir to the spiritual path, Suddhodana tried to shield the boy from all sorrow and hardship. He ordered that Siddhartha live a carefully protected life of comfort and pleasure inside the palace walls, surrounded only by youth, beauty, music, and celebration, so that he remained ignorant of illness, old age, and death. At the age of sixteen, Siddhartha was married to the graceful and intelligent princess Yasodhara, and in time they had a beloved son, Rahula, whom the king hoped would bind the prince more firmly to royal life and to the responsibilities of his lineage. Yet even amid such splendor, a quiet restlessness began to stir in his heart.

Four Encounters

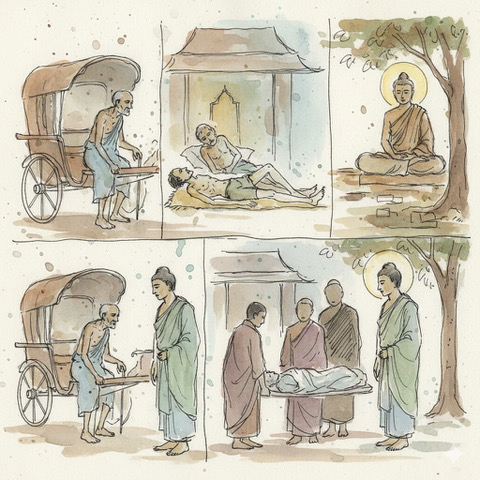

Prince Gautama Siddhartha, in the spring of his twenty-ninth year, grew increasingly troubled in spirit and longed to see the world beyond the sheltered luxury of his palace. Hoping simply to enjoy the beauty of the flowers in bloom, he instead encountered scenes that revealed to him the deeper realities of human existence. On the first day, as he departed through the eastern gate, he was struck by the sight of a frail, bent, and aging man—an image that confronted him with the inevitability of old age. On the second day, leaving by the southern gate, he saw a man wracked with severe illness, and the suffering etched on the man’s face left Siddhartha unsettled. On the third day, passing through the western gate, he came upon a lifeless corpse surrounded by grieving mourners, and the stark truth of mortality weighed heavily on him. Finally, on the fourth day, travelling northward, he encountered a wandering mendicant monk, serene and free from worldly attachments. Inspired by the monk’s calm presence, Siddhartha realized that a different path existed—one that sought freedom from suffering rather than temporary comforts. This final encounter stirred a profound resolve within him, setting him on the journey that would ultimately lead to his enlightenment.

Departure from Palace

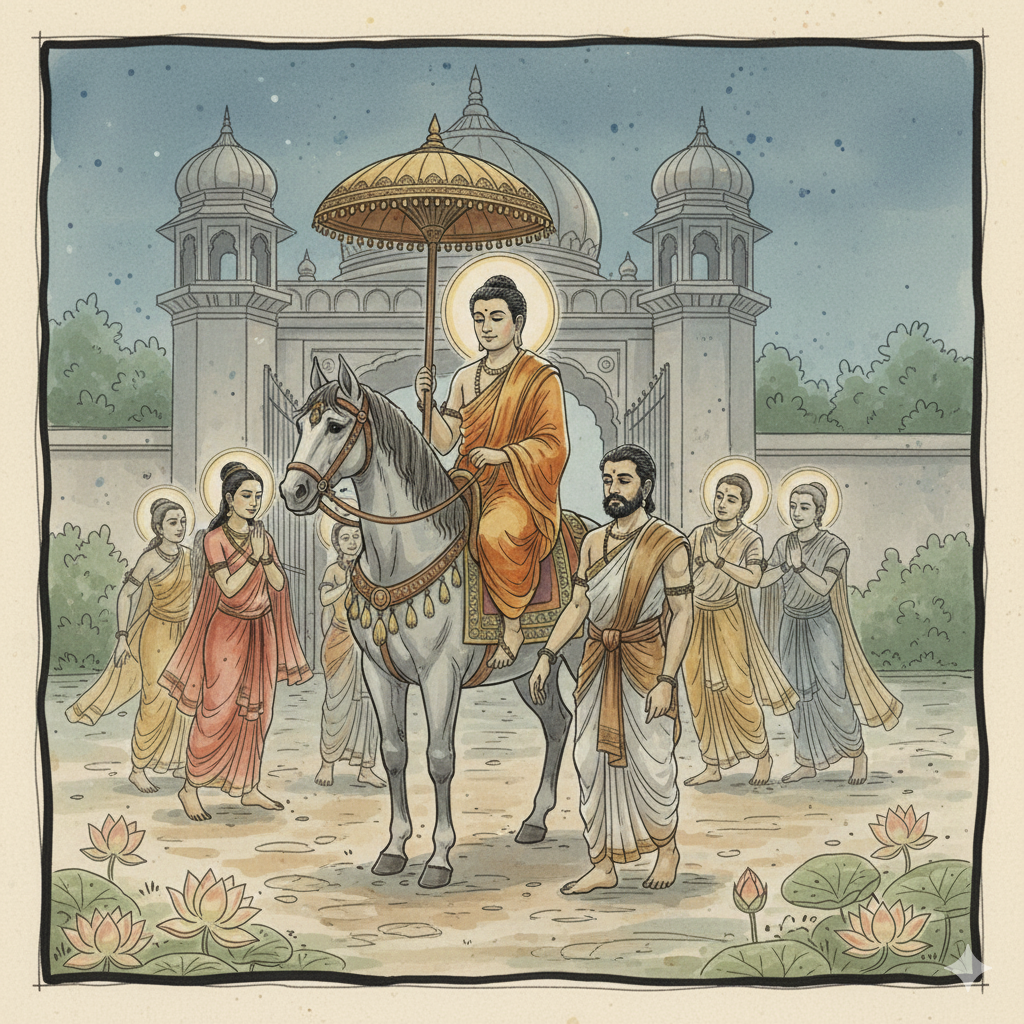

Now fully aware of the sorrow that pervaded the world outside the sheltered life of the palace, Sakyamuni resolved to abandon his opulent life as a prince, vowing instead to seek through fasting and meditation a way to relieve the sufferings of humankind.

Fearing that his father would try to prevent his departure, he decided to leave secretly at night. The king's guards fell into a deep sleep, and four nature spirits (yakshas) lifted the Prince's horse Kanthaka into the air, so that his hooves would make no noise on the cobblestone pavement.

As an ascetic in the Himalayan Mountains, the former prince lived an austere life of self-denial -- fasting, subjecting his body to strict discipline, meditating in the lotus position in all weather.

Yet after six years, enlightenment still eluded him. He came down from the mountains, bathed, and sat beneath a pipal tree at Gaya, vowing not to move from that spot until he attained full enlightenment.

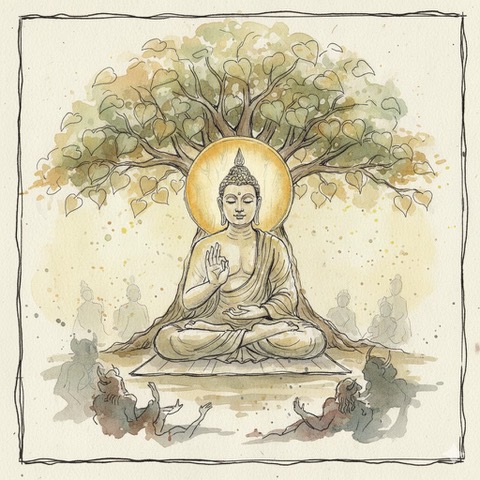

Enlightenment of Buddha

As Sakyamuni meditated beneath the tree, a light began to shine from his forehead over all the earth.

Mara, the Evil One, shuddered, he knew that his power to mislead humankind was threatened. Deciding to confront his opponent directly, Mara sent a host of demons to destroy him

Some, Mara's daughters, appeared as beautiful women, bent on distracting or seducing Sakyamuni. Others assumed the forms of fierce animals. But their roars, threats and temptations failed to move the meditating Sakyamuni, and their weapons melted away into lotus blossoms.

Finally, at age 35, on the night of a full moon, Sakyamuni attained enlightenment. (From this time forward, the pipal tree under which he sat would be known as the Bodhi tree, or tree of enlightenment).

As he was alone with no one to witness this momentous event, he called the Earth itself to be his witness by touching the ground with his right hand in a gesture known as the Bhumisparsa mudra.

Teachings of Buddha

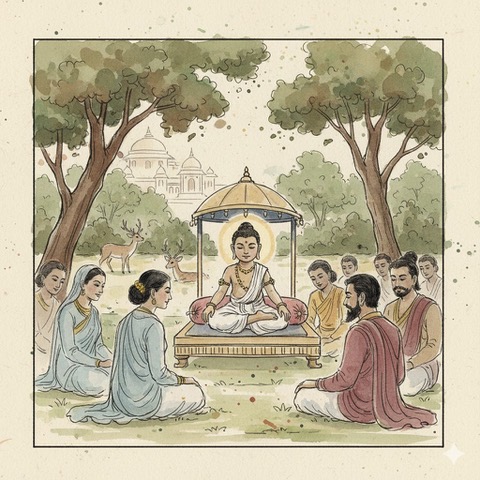

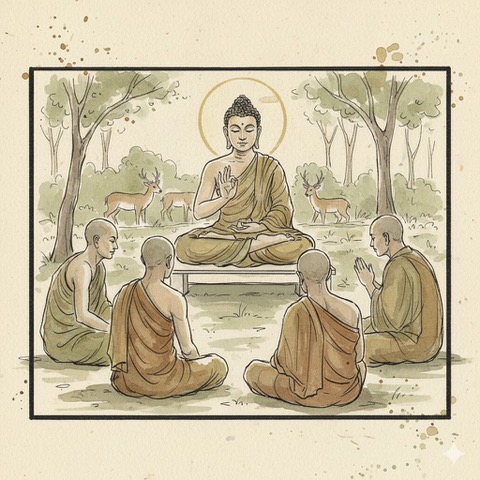

"The first sermon"

The Enlightened One gave his first public sermon in the Deer Park at Sarnath, near Benares, setting in motion the wheel of the dharma (or spiritual law) as he expounded the doctrine of the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. This first sermon is represented by the dharmachakra mudra, a two-handed gesture symbolizing the setting in motion of a wheel. This mudra is also used to show the Buddha in his role as a teacher.

"The Four Noble Truths"

In his first teaching, the Buddha expounded the basic doctrine of the Four Noble Truths. He first declared what he had learned the day he left the palace; namely, that suffering is universal and inevitable. In the Second Noble Truth, he explains that the immediate cause of suffering is desire. The ultimate cause of suffering, however, is ignorance concerning the true nature of reality. The Third Noble Truth encourages humanity, asserting that there is a way to dispel ignorance and relieve suffering. This path is detailed in the Fourth Noble Truth in the form of the Eightfold Path.

"The Eightfold Path"

According to the Buddha, the Eightfold path is the means to achieve liberation from suffering. Specifically, this path includes (1) Right View (2) Right Thought (3) Right Speech (4) Right Action (5) Right Livelihood (6) Right Effort (7) Right Mindfulness (8) Right Concentration

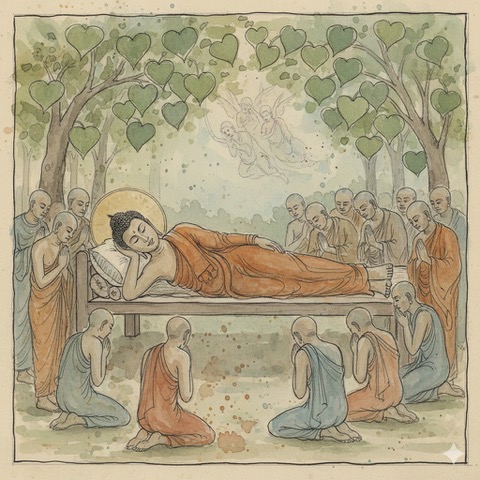

Parinirvana of Buddha

At the age of eighty, after forty-five years of teaching and guiding countless followers, the Buddha entered a deep and serene trance and passed peacefully away in the Sala Grove at Kushinagara. This moment, known as the Mahaparinirvana, is traditionally depicted with the Buddha reclining gently on his right side, calm and composed even in his final moments, while sorrowful disciples and attendants gather around him in grief. In some portrayals, his body is shown already wrapped in layers of muslin as his devoted attendant Ananda prepares for the funeral rites. According to tradition, when the Buddha’s coffin was placed upon the funeral pyre, it remained untouched by ordinary flames; instead, a miraculous fire arose from within, burning steadily for seven days until his earthly form was reduced entirely to ashes. These sacred remains, known as sharira, were then divided into eight portions and distributed to various rulers and communities across the region. Each recipient enshrined the relics with deep reverence in specially constructed mounded monuments called stupas, which soon became important centers of devotion. Over time, these stupas served not only as places of worship but also as the spiritual and architectural heart of many Buddhist monasteries.